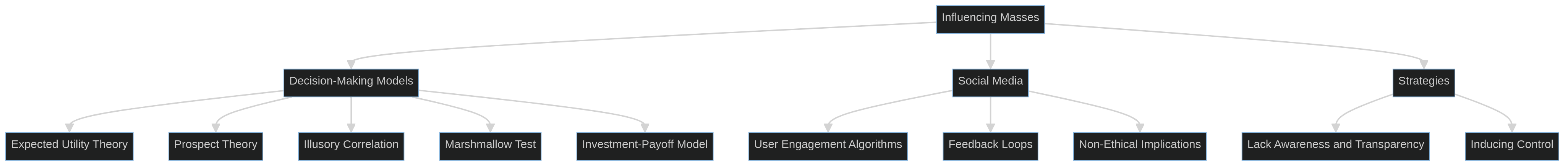

Today, we look at how social media sites use complex decision-making models and psychological biases to influence what users do. The article looks at how decision theory has evolved, from expected utility theory to prospect theory. It also looks at how manipulation techniques have changed, from TV advertising to the sophisticated algorithms used by social networks. We look at concepts like 'illusory correlation' and 'delay of gratification' to see how users are nudged towards specific ideologies without realising it. Economic models like the Investment-Payoff Model show why companies focus on engagement over diverse viewpoints, which ultimately creates echo chambers. The discussion looks at the ethical issues around these manipulations and questions the responsibility of social media corporations in shaping public discourse. We need to think about how users can counteract algorithmic influence and reclaim critical thinking in the digital age.

I. Introduction

In today's digital age, social media platforms have become really powerful tools that affect not just what we see, but also how we think. I've noticed a recent trend where users, myself included, seem to be nudged towards specific viewpoints – often without realising it. I started wondering: Are these platforms deliberately influencing our decision-making processes? This isn't just a random thought; it seems like there's a bigger, algorithmic plan to influence how users behave in ways that make it harder to think critically and push us towards certain ideologies. But what's behind this influence?

To get to grips with this, we need to look at theories from fields like mathematics, psychology and economics. The concepts of illusory correlation (where people falsely associate unrelated events) and delay of gratification (the ability to wait for a more significant reward) from psychology help us understand how algorithms exploit our cognitive biases. Economic models that maximize user engagement and profit also show us why these manipulations persist. This blog article aims to explain how decisions, which were once considered personal and rational, are now shaped by hidden forces operating within social networks.

II. Decision and Choices: Decision-Making Models

|

|

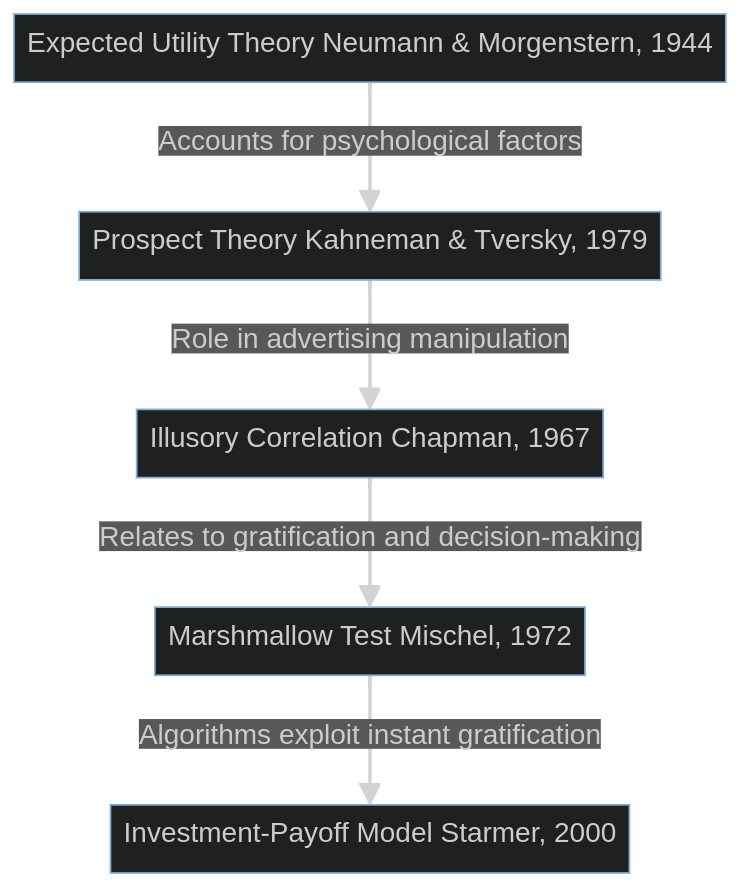

The study of decision-making has been around for a long time. One of the first and most important theories is the Expected Utility Theory, created by von Neumann and Morgenstern in 1944. It shows how people make choices when they don't know exactly what the outcome will be. This theory is based on mathematical decision theory and says that people make rational decisions to get the best outcome for them. This model works well in a structured environment, but it doesn't always apply in a world dominated by fast-paced social media. The 20th century saw the introduction of Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) [2], which takes into account the psychological factors that Expected Utility Theory overlooks. Prospect Theory suggests that people aren't always as rational as we think. They often make decisions based on perceived gains and losses, and they often overestimate risks. These insights were used by advertisers on TV, where commercials started subtly influencing viewers by creating emotional stories that made products or brands look more appealing. The psychological concept of illusory correlation, coined by Chapman in 1967, also plays a role here, where consumers mistakenly think there's a link between the products advertised and the positive outcomes shown. |

With the rise of the internet, this manipulation took on new forms. The algorithms on social media platforms are designed to keep us engaged by feeding us content that exploits our natural tendency to want instant gratification. Psychological experiments like the Marshmallow Test (Mischel, 1972) show how hard it is for people, especially children, to wait for something they want – and these platforms take advantage of this by offering lots of quick, dopamine-inducing things to look at. This makes it easy to fall into "filter bubbles", which reinforce our beliefs and narrow the range of ideas we encounter.

These algorithms have now become even more sophisticated, designed to predict and influence behaviour on an unprecedented scale. By looking at a lot of user data, companies like Facebook and TikTok have created models that show them what content each user likes, often at the cost of hiding different views. Economic models, such as the Investment-Payoff Model (Starmer, 2000) [5], show why social media giants show content that gets users engaged for longer than balanced or diverse viewpoints – because the longer we stay engaged, the more profit they make.

III. Discussion

What does all this mean for users today? The models we've looked at so far – which are based on decision theory, psychology and economics – aren't just theoretical. They're actually used by social media platforms to influence the choices we make. The more we interact with the platform, the more it reinforces our existing beliefs through targeted content, effectively narrowing our worldview. To some extent, the algorithms strip away the nuances of critical thinking, boiling complex issues down to simple, binary choices.

The idea of an illusory correlation helps us understand why misinformation spreads so quickly on these platforms. Users wrongly link specific posts or sources with credibility because they fit with their existing beliefs. This reinforcement creates a dangerous feedback loop where people who disagree are ignored and controversial ideas – whether valid or not – are either normalised or demonised based on what the majority wants.

From an ethical standpoint, this is a big problem. Should private companies be allowed to shape public discourse like this? Are they responsible for the societal consequences of their algorithms? And how do we, as individuals, take back control in a world where our thoughts and behaviours are subtly influenced by unseen forces? These are important questions that we need to think about more as we continue to grapple with the rise of algorithmic manipulation.

IV. Conclusion

To sum up, we've looked at how decision-making theories have changed and how social media algorithms use these models to influence user behaviour. From the early mathematical models to the psychological insights like delay of gratification and illusory correlation, it's clear that social networks are not neutral platforms. They're designed to influence our choices in ways that benefit their bottom line, often at the expense of open discourse and critical thinking.

Going forward, it's important for users to be more aware of these manipulations and develop strategies to counteract them. This might involve curating a more diverse set of sources, questioning the content we engage with more consciously, and pushing for greater transparency from the platforms themselves. Only by acknowledging these hidden forces can we hope to take control of our digital lives.

V. References

[1] von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press. ISBN: 978-0691130613

[2] Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. DOI: 10.2307/1914185.

[3] Chapman, L. J. (1967). Illusory Correlation in Observational Report. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(1), 151-155.

[4] Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E. B., & Raskoff Zeiss, A. (1972). Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(2), DOI: 10.1037/h0032198

[5] Starmer, C. (2000). Developments in Non-Expected Utility Theory: The Hunt for a Descriptive Theory of Choice under Risk. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(2), 332-382. DOI: 10.1257/jel.38.2.332.

[6] O'Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN: 978-0553418811

Image source 1: @prateekkatyal hosted on Unsplash.com. Retrieved: 2024-09-13.

Image source 2,3: Created by author.